by Nora (Noni) Caflisch

This paper will explore the Satir Model of therapy and the transformational change brought about in an individual’s personal growth through involvement in the Satir Systemic Brief Therapy.

Virginia Satir, the creator of Satir Systemic Brief Therapy, was born in Wisconsin in 1916. Her career as a therapist spanned forty-five years until her death in1988. She dedicated her life to helping people grow and heal. She has been sited as “one of the most influential modern psychologists and a founder of family therapy.” (www.geocities.com/socialworkontheweb/satir.html 06/08/04).

Virginia Satir’s vision was to help guide people to reach their full potential. As a therapist she developed process-oriented systems to lead people to tap into their internal resources to create external changes. She believed that people’s internal view of themselves, their sense of self-worth, was the underlying root of their problems.

Satir’s systems were all based around looking clearly and congruently inward at oneself to view how we originally learned to cope with our world. She believed that the problem was not the problem but how one coped with the problem was the problem.

Satir developed and named four stances for viewing how one copes or originally learned to survive. Her systems included family mapping, family reconstruction, the iceberg model, the parts party, a self-mandala of universal human resources, and sculpting in which a person can express, define and explain their inner landscapes. This paper will follow an individual’s personal growth through their involvement with and learning of the Satir approach to therapy.

Virginia Satir “shied away from the illness-centered approach of the Freudian school of psychology, and instead placed emphasis on personal growth.”(www.plebius.org/Virginia+Satir 06/08/04). She developed a personal and unique style of therapy over the course of her forty-five year career. At the core of her beliefs was that all behavior was learned and therefore could be unlearned making personal growth and change possible. Her vision was to help people to reach their full potential. She encouraged people to “find what she called their wisdom box-their sense of worth, hope, acceptance of self, empowerment, and ability to be responsible and make choices.” (Satir et al., 1991 p.4)

She believed that to heal the self, to heal the family, was ultimately to heal the world. To this end she formed the Avanta Network. Almost twenty years after her death, Avanta and its affiliate organizations all over the world continue Satir’s work in training, supporting and encouraging therapists, individuals and organizations towards personal growth and ultimately world growth.

The Satir growth model is based on her belief that humans have the “ability to change, expand, and manifest growth. Along with love, discovery of and the freedom to express one’s feelings and differences are major components of the model.” (Satir et al., 1991 p.16)

Satir’s therapeutic beliefs form the basis of her growth model. Her “growth model looks at human beings in the form of wholeness -the integration between body, mind, and spirit-the fundamental characteristic of the universe.” (Cheung, M., 1997) The common beliefs and principles of the Satir growth model are as follows:

- Change is possible. Even if external change is limited, internal change is possible.

- Parents do the best they can at any given time.

- We all have the internal resources we need to cope successfully and to grow.

- We have choices, especially in terms of responding to stress instead of reacting to situations.

- Therapy needs to focus on health and possibilities instead of pathology.

- Hope is a significant component or ingredient for change.

- People connect on the basis of being similar and grow on the basis of being different.

- A major goal of therapy is to become our own choice makers.

- We are all manifestations of the same life force.

- Most people choose familiarity over comfort, especially during times of stress.

- The problem is not the problem; coping is the problem.

- Feelings belong to us. We all have them.

- People are basically good. To connect with and validate their own self-worth, they need to find their own inner treasure.

- Parents often repeat the familiar patterns from their growing up times, even if the patterns are dysfunctional.

- We cannot change past events, only the effects they have on us.

- Appreciating and accepting the past increases our ability to manage our present.

- One goal in moving toward wholeness is to accept our parental figures as people and meet them at their level of personhood rather than only in their roles.

- Coping is the manifestation of our level of self-worth. The higher our self-worth, the more wholesome our coping.

- Human processes are universal and therefore occur in different settings, cultures, and circumstances.

- Process is the avenue of change. Content forms the context in which change can take place.

- Congruence and high self-esteem are major goals in the Satir model.

- Healthy human relationships are built on equality of value. (Satir et al., 1991 p.16)

As stated above one of the major goals of the Satir growth model is high self-esteem. Though Satir used the terms self-worth and self-esteem interchangeably, the author does not agree that these terms hold the same meaning. Satir defined self-worth and self-esteem as “the ability to value one’s self and to treat oneself with dignity, love, and reality.”(Satir, 1988, p.22) The author agrees that while the above definition is for self-worth, self-esteem is much less intrinsic. The author maintains that a person could hold them self in a very high level of esteem and yet have a very low sense of self-worth. For the purpose of this paper, the term self-worth will be used. Satir also uses the term “pot” to refer to a person’s feeling of self-worth. This term grew into a metaphor for self-worth from a story she would tell about a huge black iron pot that was used for a variety of purposes in her family home. The family question was “What is the pot now full of and how full is it?” (Satir, 1988, p.20) In her practice “as with my old family pot, the questions are: is my self-worth negative or positive at this point, and how much of it is there?” (Satir, 1988, p.21) Satir believed people that feel little self-worth open their way to becoming a victim, they depreciate themselves and they depreciate others. In doing so they create a psychological wall around themselves, hide behind and then deny that they are doing it. In Satir’s growth model, her goal was to help a client reach their own source of personal energy by sifting through all the internal messages and stored resentments that stood as a psychological wall in the way of the client’s positive feelings of self-worth.

“When I approach the matter of making change, I look in four directions:

- How do I feel about myself? (Self-esteem)

- How do I get my meaning across to others? (Communication)

- How do I treat my feelings? Do I own them or put them on someone else? Do I act as though I have feelings that I do not or that I have feeling that I really don’t have? (Rules)

- How do I react to doing things that are new and different? (Taking risks)

“One change already influences other parts. That means we can start anywhere..” (Satir, 1976) “Congruent communication holds the opportunities for developing self-worth.” (Satir et al., 1991 p.111)

Satir held that “the power in congruence comes through the connectedness of your words matching your feelings, your body and facial expressions matching your words, and your actions fitting all.” (Satir, 1976)

To achieve a congruent stance was the ultimate goal of Satir therapy and will be discussed further in the section on coping stances. She believed that a growing awareness of language and communication would lead to increased congruence “because language reflects a person’s cognition and affect, changing one’s language changes one’s perception.” (Cheung, M. 1997)

Satir thought that even paying close attention to how one uses the words I, You, They, It, But, Yes, No, Always, Never, and Should would be a step towards becoming more congruent. Satir maintained that communication was “the largest single factor determining what kind of relationship one makes with others and what happens to one in the world.” (Satir, 1972, p.30)

“One of the most important approaches of Satir’s model is the focus on question and answer approach regarding what one sees, what feelings one has, what feelings follow the initial feelings, and what meaning one makes of it becomes a major tool with which to transform old coping patterns into more congruent, healthy relationships.” (www.web8.epnet.com 03/08/04) Satir believed that coping patterns learned initially in the family setting often became our problem as adults or in the family we produce. “Problems are not the problem; coping is the problem. Coping is the outcome of self-worth, rules of the family systems, and links to the outside world.” (www.plebius.org/Virginia+Satir 06/08/04)

Satir developed what she called survival stances to demonstrate how people cope with problems. The four survival stances are placating, blaming, being super-reasonable, and being irrelevant. She thought that these stances “originated from a state of low self-worth and imbalance, in which people give their power to someone or something else. People adopt survival stances to protect their self-worth against verbal and nonverbal, perceived and presumed threats.” (Satir et al., 1991 p.31) She illustrated each of the stances in a circular diagram divided into thirds with context, self and others each taking up one-third of the circle. She also developed body positions to illustrate each of the stances. When the subjects were physically sculpted into their stance the feelings generated in the overall family sculpt were explored.

Placating

A person who has a placating stance views others and context to hold more value than their own true feelings. They are nice when they do not feel nice, they take the blame when things go wrong, they try to alleviate others problems and pain. Their inner monologue sounds like- “I am not important.”

"Everything is my fault." "I should always do for others."

“In a typical placating stance, we kneel, extend one hand upward in supplication, and clamp the other hand firmly over our heart. This gesture exemplifies that “I want to do everything for you, and if you see me protecting my heart, maybe you won’t kill me.” ” (Satir et al., 1991, p.37) (Satir et al., 1991 p.38)

Physiological affects that placators typically experience are digestive tract disorders, migraines, and constipation.

Blaming

A person who has a blaming stance discounts others and counts only the self and context. They hold the belief that they must not be weak, they harass and accuse others for continually making things go wrong. Their inner monologue sounds like-

"If it wasn't for….I wouldn't be in this mess." "I'll beat the…out of you!

In the blaming physical sculpt, “we stand with our back straight and point a fully outstretched finger at someone. To help scare people, we put one foot out; to balance, we put the other hand on our hip. We raise or furrow our brow, and we tighten our facial muscles.” (Satir et at, 1991 p.43) A blamer typically draws in a skimpy breath to accommodate their loud and vigorous shouting. Starved for oxygen their muscles and tissues tighten. A typical physiological complaint of a blamer is chronic stiffness due to rapid and shallow breathing.

(Satir et al., 1991, p.42)

Being Super Reasonable

A super reasonable person discounts self and others and respects context only. They frequently know lots of data and function from a logic only perspective. Their inner monologue sounds like-

"Everything is just a matter of logic, emotions are a waste of time." "I must be more intelligent and show how intelligent I am."

In the super reasonable stance “we stand stiffly erect and immobile, with both arms at our sides or folded symmetrically in front of us…our faces appear expressionless. When people speak to us, we pontificate at length, seemingly wise and stately.” (Satir et at, 1991 p.45) Physiologically this stance restricts the glandular secretions. “Breast milk, semen, sweat, tears, and mucus are not created freely when we are super-reasonable….The juices are drying out.”

(Satir et al., 1991, p.47)

Being Irrelevant

A person that is irrelevant discounts self, others and context. An irrelevant person is often seen as amusing or a clown. They can distract attention away from any stressful situation. Their internal monologue will be about anything other what is happening before them. They are physically active and inattentive by whistling, singing, blinking or fidgeting. The irrelevant stance will hold their bodies askew, in “a hunched yet standing posture, both her knees are facing in and both arms and hands are facing up and out. Her head is cocked severely to one side, both eyes bulging. Her mouth is gaping and twisted and many parts of her face are twitching.” (Satir et al., 1991, p.51) A person with an irrelevant stance moves inappropriately, in a hyperactive way and their movements are usually purposeless. The physiology of this stance usually affects the central nervous system. A person in a chronic stance of irrelevance can have a distinct feeling of imbalance that includes dizziness and in severe cases includes psychosis and hebephrenia.

(Satir et al., 1991, p.50)

A person’s stance of choice is formed in childhood based on what we learn or are taught, mostly non-verbally from people’s double-level communication, about what family rules are in operation. For any of the stances to work the other people in the relationship must be functioning from one of the other four stances. Should one of the people function from a congruent stance then the other four stances loose their strength and change must occur.

Congruent

The ultimate goal of the Satir growth model is congruence. Satir held that high self-worth and congruence are the main “indicators of more fully functioning human beings.” (Satir et al., 1991, p.65) The congruent person holds equal balance in the circle of self, others, and context. “When we decide to respond congruently, it is not because we want to win, to control another person or a situation, to defend ourselves, or to ignore other people. Choosing congruence means choosing to be ourselves, to relate and contact others, and to connect with people directly.” (Satir et al., 1991, p.66) “Congruent communication has no contradictions between its layers. Senders do not consciously or unconsciously expect the receiver to make inferences about what they did not say, or to perceive contradictions between verbal and non-verbal messages. Congruent communicators share their thoughts and emotions about themselves without projecting them onto others and thus avoid manipulation.” (http://web18.epnet.com 03/07/04) Satir believed that there were three levels to congruence. The level of feelings, the self, and the life force or spiritual make up the three levels of congruence.

A person is not locked into one stance. They will have a more prominent stance under stress or in dealing with specific relationships. All of these stances contain positive aspects, as well as the more negative traits as listed previously, that provide resources from which to grow. Placators are kind and caring people, blamers can be assertive, super-reasonables can be intelligent, and irrelevant people can be creative and flexible. As change and growth occurs another coping method could be activated although “we are confined to some form of placating, blaming, being super-reasonable, or being irrelevant unless we learn how to be congruent.” (Satir et al., 1991, p.53) As children we learn to function in one of these stances primarily in order to be part of a balance in the family. With the best of intentions parents do the best they can, based on what they learned from their family of origin. Many of these learnings are based on generations of miscommunication. This is where Virginia Satir developed and used a three generational family map with which to explore issues, relationships and re-occurring themes in families. This was not designed to accuse or blame but rather to view situations from an empathetic point of view to understand previous situations that influence our situation today.

“Family sculpture was one of Virginia’s well-known ways of transforming words into action. It helped her depict the family’s system of interaction so that family members could see themselves more clearly. She would position family members in a still tableau or sculpture that displayed their typical ways of interacting- their supporting, clinging, blaming, placating, including, excluding, their distance and closeness, power and contact relationships, etc.” (Andreas, 1991, p.15) These dramatizations provided family members an opportunity to gain insights into their repetitive patterns with each other and through skillful interaction with the therapist/guide they learned to communicate more congruently with each other.

In family therapy, these sculptures use the actual members of the family although she found that these same techniques work when working with an individual. With an individual, others are asked to play the roles of the family members. Previous work would have been done with the individual’s, the Star’s, generational family map to familiarize the therapist/guide with “family rules of parents and grandparents, family patterns (e.g. occupations, illnesses, coping stances…) family values and beliefs…family myths and secrets, family themes.” (Satir et al. 1991, p.372) Along with the family map, the Star is also asked to make a chart of their wheel of influence. With their own name in the middle, the Star then surrounds their name with circles representing other people that played a significant role in their development. The wheel of influence is also used as a resource in the family sculpts.

Another resource used by Satir was the personal iceberg metaphor. In Satir’s iceberg model a person’s behavior is the tip of the iceberg and at the water line is the person’s coping stance. She maintains that becoming familiar with one’s under the waterline, bulk of the iceberg is the path to becoming congruent. She described three levels of congruence. The first level under the waterline to become aware of and familiar with is one’s feelings, expectations, perceptions and yearnings. The second level is awareness, acceptance and experience, the knowledge of self-wholeness. The third level is of spirituality and universality. Since Satir’s death, Dr. Banmen, who studied under Satir, has further delineated the iceberg model.

His view of The Personal Iceberg Metaphor of the Satir Model is as follows:

Many of the feelings, perceptions, and assumptions that we hold are formed originally from our family rules. These rules come from being taught directly or formed through assumptions and interpretations of interactions both verbal and non-verbal. “Satir emphasizes that the rules are an essential controlling force in the family…. Messages that parents convey to the child are often based on their own self-worth and in this way the interactive and reactive establish themselves for the next generation.” (http://web8.epnet.com 03/08/04)

When members of the same family express and examine what they each as individuals hold as family rules, there can often be great variations on what each of them knows to be true. Family rules are intended to provide guidance, set limits and to socialize. But family rules also serve to keep “the closed family system operating. A closed system, according to Satir, is characterized by members who:

- Are guarded with each other

- Are hostile

- Feel powerless and controlled and are passive

- Are inflexible in their views and behaviors

- Wear a façade of indifference toward each other

Symptoms appear when the family’s rules squeeze a member’s self-worth to such a point that his or her survival is in question.” (Satir et al., 1991, p.112) It becomes easy then “to mix up our personality with our rules for how to live… Once we cut off our feelings or say only certain feelings are okay, we rechannel our energy away from our own experiences of the world, suppress or fight our feelings, and follow our rules as best we can.

In this case, the energy gets rechanneled into physical, psychological, or social difficulties.” (Satir et al., 1991, p.303) Family rules often include rules about feelings, which feelings are all right to express and which feelings should never be discussed. Rules about not asking for what you want. From these rules and a host of others, people grow up believing that they cannot say what they feel only what they think that they are supposed to feel, that they cannot ask for what they want but they must ask for what they think is expected of them to ask for.

As adults many of us function within our original family rules even if they no longer fit our needs or situation. When these family rules become barriers in our lives or the lives of our family members it is time to examine and transform these rules into guidelines. Satir believed that it was important not to throw out the rule because most likely it had been based on some original wisdom, rather to move the rule from “compulsion to choices.” (Satir et al., 1991, p.307)

Satir would then lead her client through three stages of transformation. Changing the shoulds to cans, the nevers to sometimes, and the third step is to expand the “I can” into three possibilities of what the person can do. “When inhuman rules can be changed into human ones, the family and the individual can operate within the Five Freedoms.” (Satir et al., 1991, p.307) Satir saw the five freedoms as a person’s rights and responsibilities.

The Five Freedoms

The freedom to see and hear what is here instead of what should be, was, or will be.

The freedom to say what one feels and thinks, instead of what one should.

The freedom to feel what one feels, instead of what one ought.

The freedom to ask for what one wants, instead of always waiting for permission.

The freedom to take risks in one's own behalf, instead of choosing to be only "secure" and not

rocking the boat. (Satir, V. 1976)

Virginia Satir believed change was possible. Her focus was on connecting her client or the family she was working with, at the level of yearnings, expectations, perceptions, and feelings. Working from this level would result in a sharing, acceptance, and respect as a matter of individual choice. Through the processes described previously, the client or family would learn the steps to becoming more congruent with each other. This work would provide an internal shift for the individual or family members that would fundamentally affect each person’s self-worth. Change then would be an internal shift that would bring about an external change. “To transform the survival stances into congruent communication, or to effect any other change, we need to examine the concepts of discovery, awareness, understanding, and new applications.” (Satir et al., 1991, p.86)

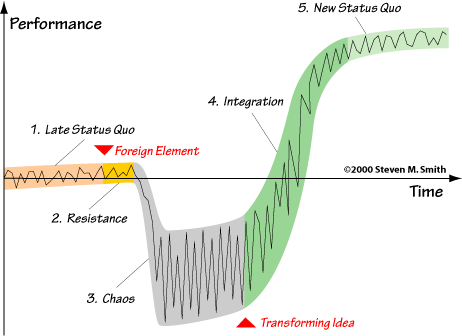

Satir delineated six stages in the process of change. The first is the client’s status quo or existing state. For an individual or a family system this is the place of familiar patterns of expectations and reactions. Dysfunctionally balanced individuals or family systems will continue to cope by placating, blaming, being super-reasonable, or being irrelevant until something drastic happens. The second stage is the introduction of a foreign element; the something drastic that signals the need for change is recognized. When an individual or family system is faced with something drastic they seek help. The incident and the therapist they seek, both become the foreign element. This is the stage where expectations, barriers to change, and coping stances are examined using the processes described previously. Resistance can be very strong at this stage. Reframing resistance, looking at the positive resources that an individual’s coping stance has provided, leads to a place of acceptance and dignity. With dignity in tact, a place to feel secure enough to move into the next stage of change is provided. The third stage is chaos where the client begins to move from their status quo into a state of disequilibrium. “Chaos means the system is now operating in ways we cannot predict. For many members, not being able to foretell their family’s expectations and reactions means they have lost their security and stability. They are in limbo, sometimes paralyzed by their fear of destruction. They may also feel a sense of loss or impending loss and consequently panic.” (Satir et al., 1991, p.108) Satir’s recognition and use of this stage of chaos is considered one of her major contributions. “Satir discovered that without this stage of chaos, no profound transformation of old, familiar survival copings could occur. Attaining positive, healthier, and more functional possibilities requires moving through a period of chaos.” (Satir et al., 1991, p.114) The fourth is the integration of the new learnings and where a new state of being begins to evolve. In this stage old survival patterns dissipate as new more congruent perceptions and possibilities develop. This is where the individual or family system takes “charge of what we once did on automatic pilot, bringing our control back into consciousness, and becoming more responsible for our internal process of Self.” (Satir et al., 1991, p.114) The fifth stage is practice, where the new learnings are practiced and the new state of being is strengthened. At this stage Satir encouraged clients “to use amulets, affirmations, meditations, and anchoring exercises to reduce the lure of past patterns” (Satir et al., 1991, p.115) so that their new more congruent state becomes automatic. A new status quo then becomes the sixth stage and represents a more functional state of being. This new status quo is a place of new self-images, hopes, dreams, and well-being. “Our challenge now is to develop human beings with values: moral, ethical, and humanistic. For me, this means learning how to be congruent, and that leads to becoming more fully human. When we achieve that, we will be able to enjoy this most wonderful planet and the life that inhabits it. – Virginia Satir” (www.sbbbks.com/satir-life.htm 14/07/04)

“Satir highly recommends that all therapists using her model have their own family reconstruction experience. This reduces the personal blindspots and defenses of a therapist while dealing with struggles of the family members” or individuals. (http://web8.epnet.com 03/08/04) She maintained that it was important for therapists to have done his or her own personal work to avoid having the client’s issues become enmeshed with the therapist’s issues. Satir held that therapists must be a model for congruency with his/her clients and only through having done his or her own personal work could this congruency be achieved. To keep growing and learning was the way for therapists to stay energized and to avoid “burn-out.” “I have learned that when I am fully present with the patient or family, I can move therapeutically with much greater ease. I can simultaneously reach the depths to which I need to go, and at the same time honor the fragility, the power and the sacredness of life in the other. When I am in touch with myself, my feelings, my thoughts, with what I see and hear, I am growing toward becoming a more integrated self. I am more congruent, I am more “whole,” and I am able to make greater contact with the other person.” (Baldwin and Satir, 1987, p.23) Contact is a means of dealing honestly, sharing your human issues and concerns, maintaining integrity and nurturing your growing self-worth. “The more full and complete the contact that we make with ourselves and each other, the more possible it is to feel loved and valued, to be healthy and to learn how to be more effective in solving our problems.” (Satir, 1976) The rest of this paper will document an individual’s transformational change and personal growth through involvement in the Satir Systemic Brief Therapy over the course of a six-month period.

CHAPTER III:

METHODOLOGY

IntroductionThe purpose of this study was to document the transformational change and personal growth of the author through involvement in the Satir Systemic Brief Therapy training. I attended ten, one-day Satir workshops over a seven-month period. Phenomenology explores lived experience and was chosen as the most appropriate method for this personal study. Chapter III will provide a brief description of phenomenology and the particular procedures chosen to track and acknowledge the transformational changes and personal growth that occurred over the course of the involvement with Satir training. Personal beliefs, previous knowledge and limitations of the study will be discussed.Phenomenology As A Methodology “To deny the truth of our own experience in the scientific study of ourselves is not only unsatisfactory, it is to render the scientific study of ourselves without a subject matter….Experience and self-understanding are like two legs without which we cannot walk.”-Francisco Varela (http://www.findarticles.com 29/12/04)

“As formulated by Husserl (the founder of phenomenology)…phenomenology is the study of the structures of consciousness.” (http://www.mala.bc.ca 15/01/05) Phenomenology is the examining of the lived experience. In the case of this study it was used to examine the lived experience of the author in her learning of and applying the models used in Satir Systemic Brief Therapy training. Husserl advocated “bracketing (i.e. setting aside preconceived notions) enables one to objectively describe the phenomena under study.” (http://www.findarticles.com 29/12/04) Martin Heidegger, a follower of Husserl, “believed that as human beings, our meanings are co-developed through the experience of being born human, our collective life experiences, our background, and the world in which we live….He did not believe it was possible to bracket our assumptions of the world, but rather that through authentic reflection, we might become aware of many of our assumptions.” (http:www.findarticles.com 29/12/04) In Max Van Manen’s book, Researching Lived Experience, he warns that all accounts of the lived-experience are already transformations of those experiences (p.54), but that “the ‘data’ of human science research are human experiences.” (p.63) Phenomenological methods of research include interviews, observations, recollections, diaries, journals, logs and letters.

Research Methods In order to understand the personal transformational phenomena being studied I will try to capture an internal snapshot of self prior to Satir training. I will use previous diary/journal notations and reflections on self as well as use Satir’s iceberg model to formulate a picture of where I am starting in this process. I will process myself through Satir’s iceberg model periodically throughout the seven-month period as a record of process. I can draw from a written collection of comments/reflections made by people that are close to me about how they see me. This collection is from previous to, during and following the Satir training. Following each of the workshop weekends, I will keep a personal reflective journal on my learning’s and working within my triad on the particular lessons presented. At the end of my Satir training, I will examine this collection to see if any themes of transformation emerge.

The main goal, as I see it, in Satir training is growing towards being a congruent person. “Congruence is based on an awareness of what is going on within: our thoughts, feelings, body messages, and the meanings we ascribe to our experiences. We learned to be incongruent to survive; to learn congruence requires reevaluating and hearing ourselves anew, being able to gauge our self-worth at any moment, and moving from the submissive/dominant model to Satir’s growth model.” (Satir et al., 1991, p.76) The difficulty with this study is the ability to be “congruent” and objective when viewing oneself introspectively. As the viewer observing any phenomena must always consider their own belief systems and underlying preconceived notions, the limitations of this study encompass my ability to be congruent and observant of my own internal shifts as well as my own personal beliefs.

I will attempt to bracket or set aside my understandings and beliefs prior to my involvement in Satir Systemic Brief Therapy training. My personal biases, beliefs, and experiences that bracket who I am are as follows. I grew up in a white, middle-class family in the 1950’s and 60’s. My early adult life was in the typical experimental culture of the early 1970’s. I am a woman, daughter, sister, ex-wife, wife/partner, friend, mother, student and teacher. I believe I have chosen to surround myself with people and experiences in my life that have caused me to question my inner workings, reflect and grow personally. I believe that connection and relationship is of primary importance. I believe I am willing to look critically at the multi-layers of my multi-dimensional being. I believe this study to be a step in the continuum of my personal growth.

Summary The purpose of this study is to document the transformational change and personal growth of the author through involvement in the Satir Systemic Brief Therapy training. The phenomenological approach was chosen as the most appropriate approach to investigate the inner world and personal transformations. Through study of the lived experience of Satir training, the author hopes to bring new insights and hidden processes to an external awareness. Chapter four will describe the author’s process through the structures of the Satir Model (ie. iceberg, family maps and communication model) and highlight any themes that emerge.

References

Books:

Andreas, S. (1991). Virginia Satir The Patterns of Her Magic. Moab, Utah: Real People Press.

Baldwin, M. and Satir, V. (1987) The Use of Self in Therapy. New York: The Haworth Press.

Banmen, J., Gerber, J., Gomori, M., and Satir, V. (1991) The Satir Model. Palo Alto, California.

Lum, Wendy. The Lived Experience of the Personal Iceberg metaphor of Therapists in Satir Systemic Brief Therapy Training. UBC MA April 2000

Rogers, Carl. (1977) Carl Rogers on Personal Power Inner Strength and its Revolutionary Impact. New York: Delacorte Press.

Satir, Virginia. (1972) Peoplemaking. Palo Alto, California: Science and Behavior Books.

Satir, Virginia. (1976) Making Contact. Berkeley, California: Celestial Arts.

Satir, Virginia. (1983) Conjoint Family Therapy. Palo Alto, California: Science and Behavior Books.

Satir, Virginia. (1988) The New Peoplemaking. Mountain View, California: Science and Behavior Books.

Van Manen, Max. (1990) Researching Lived Experience Human Science for an Action pedagogy. London, Ontario: The Althouse Press.

Webpages:

Social Work A Work of Heart.

http://wwwgeocities.com/socialworkontheweb/satir.html

Virginia Satir Biography.

http://www.avanta.net/BIOGRAPHY/bio-family.html

Virginia Satir.

http://www.plebius.org/encyclopedia.php?term+Virginia+Satir

Virginia Satir: Her Life and Circle of Influence.

http://www.sbbks.com/satir-life.html

Banmen, J. Virginia Satir’s Family Therapy Model.

http://web8.epnet.com

Banmen, J. Changing Unmet Expectations in Therapy. http://www.satirpacific.org

Byrne, Michelle M. Understanding life experiences through a phenomenological approach to research.

http://www.findarticles.com 29/12/04

Cardwell, Maude. The Seth Material Blueprint for the New Age.

http.//www.worldlightcenter.com

11/05/02 Cheung, M. Social Construction Theory and The Satir Model: Toward a Synthesis.

http://content.epnet.com

Horn, Jim.Qualitative research literature: a bibliographic essay- Qualitative Research.

http://www.findarticles.com

Moore, M. and Kramer, D. Satir For Beginners: Incongruent Communication Patters in Romantic Fiction.

http://web18.epnet.com Phenomenology. http://www.mala.bc.ca